Colours of the Arabian

My grandfather had a beautiful black Arabian stallion. I never saw him with my own eyes as it was long before I was born, but according to my father’s vivid descriptions and stories, he fulfilled every traditional distinction of an Arabian. It has been a dream of mine to own a black Arabian, but I’ve sometimes heard it said that black Arabians are rare and not so easy to find.

That got me wondering about the different colours that Arabians can be, how common each of the colours are, and if it is actually true that black Arabians are rare and difficult to come by.

Everyone agrees that Arabian horses can be black, bay, chestnut (the three base colours), or grey; there is no debate over these four. Some also add brown, white, and roan. For example, the Arabian Horse Association in the United States accepts for registration in their stud book, black, bay, chestnut, grey, and roan.

Arabians can be found in all of these colours, but as we delve into a bit more detail, we’ll see that what looks like a straightforward colour to the eye might not be quite so. Especially once we get into how actual horse coat colours are defined and described. Sometimes the only way to truly know is by doing a DNA test — and even that might not be conclusive!

Before we get into the detail, it is important to note some common horse coat colours that do not apply to Arabians. Arabian horses are never pinto, such as piebald (black and white — think of a typical cow), or skewbald (brown and white or red and white). However liberal white markings can occur, and these could be described as particoloured.

If you are interested in how colours such as piebald are thought to occur due to domestication, there is an upcoming article on the domestication syndrome.

Black

These horses are as described: black. All the hairs are black, both on the body and the points; the points of a horse being the mane, tail, lower part of the limbs, and the rim of the ears (see Parts of a Horse). They may however have white markings, such as on the lower legs.

The coats of some black horses can become faded or sun-bleached during certain times of the year. Sometimes these can be mistaken as dark bay, dark chestnut, or brown horses, but you will be able to confirm whether they are black by looking at the hairs around the eyes, muzzle, and around the coronet band of the hoof (see Parts of a Horse). On a black horse, these hairs will be black, while on a bay, brown, or chestnut, they will be a lighter colour.

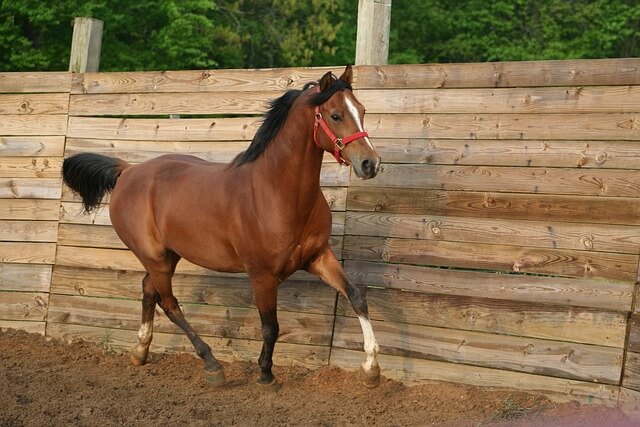

Bay

These are horses that have a brown body and black points. The brown colour comes from a mix of black and red hairs over the body, which together give a brown appearance.

The shade on the body, which may be from a very light reddish colour, through brown, to a very dark almost black colour, depends on the spread and proportion of the black and red hairs. Bay horses may also have white markings.

The key thing to remember is that the defining feature of a bay horse are its black points. The main shades of bay are:

- Black Bay: a very dark bay, almost black in colour.

- Dark Bay: as the name suggests, dark, but not as dark as a black bay. It can be confused with ‘seal brown’, which is covered below under ‘Brown’.

- Mahogany Bay: dark reddish-brown colour with black points.

- Blood Bay: a dark red bay that is almost chestnut colour but with black points.

- Brown: brown colour with black points.

Chestnut

These horses have red hairs all over the body, including the points, usually giving them a lighter colour than bay horses. However, as mentioned above, they can also get dark enough to be mistaken for faded black. The mane and tail can be a similar colour to the body, or lighter, while some have a yellowy blonde colour called flaxen.

The main shades of chestnut are:

- Liver Chestnut: a very dark chestnut that is a reddish brown colour.

- Flaxen Chestnut: a light coloured chestnut with flaxen (pale golden-yellow) mane and tail.

- Sorrel: this is an American (and particularly a Western riding) term to describe a light coloured chestnut that is the same colour all over. In other places it would probably be described as light chestnut or simply chestnut.

The Base Colours

Black, bay, and chestnut are the three base colours for all horses. As mentioned, there is an upcoming article on the basic genetics of horse colours, which is definitely worth a read and covers these and other colours. It is useful to get some understanding of the genetics for colour, as it helps you appreciate how and why the various colours occur.

Beyond the base colours Arabians can also be brown, white, and rabicano (often termed roan).

White

This is maybe the easiest one to explain. True white horses carry the dominant white gene (W), which is pretty rare all round regardless of breed. This gives the horse not only white hairs from birth, but also pink skin as opposed to black skin.

While true or dominant whites do occur amongst Arabians, they are pretty rare. When you usually come across white Arabians, they are actually nearly always grey horses that have turned completely white. One way of confirming this is to look at the skin under the hair — an easy area to do this being around the eyes. The skin will be black rather than the pink found in true or dominant whites.

Grey

Grey horses are born as one of the other base colours — black, bay, or chestnut — but their hairs turn white slowly over time, giving them a grey appearance.

Grey horses can be more accurately described by also giving their original colour, e.g. bay with grey modifier. Grey is quite common amongst Arabians.

Roan and Rabicano

The roan colour describes a horse that has an even spread of hairs of a base colour (black, bay, or chestnut) and white hairs. This is different to grey as the colour doesn’t change over time and the spread remains constant. True roan horses are born that way, and there is actually a gene that causes this. This is separate and different to the gene that causes greyness.

Most Arabians described as roan on a first glance are usually grey horses in transition, as they often have a phase where they appear roan as their coat lightens. However, for those Arabians that aren’t greys in transition, when we speak of roan, it still isn’t true roan, but rather what is properly described as rabicano.

Rabicano is a more limited spread of white hairs over the midsection and flanks of a horse rather than the whole body, and importantly, the roan gene is absent. This still gives the roan colour effect over the areas it is present, and similarly remains constant unlike grey. As the roan gene doesn’t occur in Arabians, it is safe to assume that a roan Arabian is always actually a rabicano.

Brown

This is perhaps the trickiest colour to cover as what may be described as a brown horse can actually be a few different colours genetically. Dan Sponenberg, the author of Equine Color Genetics, writes that “brown, in horse colour terminology, is used to refer to colours that are darker than bay and lighter than black.”

Unfortunately, what is considered brown to the eye of an observer is, genetically speaking, an array of different colours. It could be a very dark bay, a very dark chestnut, or a light black horse. All of these can be identified through DNA testing, and once identified you’d know that genetically, you actually had a bay, chestnut, or black horse (to be covered in more detail in the upcoming article on basic genetics).

So while many horses to a casual observer would seem to be some varying shade of brown, they could actually be defined as one of the other mentioned colours. If this is the case, then does it even make sense to talk of brown horses?

Well, there is a colour called ‘seal brown’ which describes a very dark brown, almost black coloured horse with black points, but with a lighter reddish colour (sometimes described as tan) around the eyes, muzzle, flanks, and other soft areas.

A seal brown horse is thought to be genetically different to a black, bay, or chestnut coloured horse by the fact that it carries a specific gene (a particular allele of the agouti gene) that makes it this colour. This hasn’t been fully proven yet, but if it turns out to be accurate, then this would make seal brown (genetically speaking) a distinct coat colour.

Aside from seal brown, some experts, including Dan Sponenberg, still consider brown as a distinct colour despite the lack of clear genetic proof to date. They differentiate brown from dark bay by considering whether there is black countershading on the body. This is where the upper side of the horse’s body is a darker black colour compared to the underside, which is a lighter brown colour.

This is also sometimes referred to as sooty, smutty, or sooty countershading, because it seems as if soot has been dropped on the horse from above. Countershading is thought to give animals an advantage in the wild. It can help with thermoregulation, protect from ultraviolet light, and most importantly, help with camouflage.

The darker coloured topline and paler coloured undersides act as camouflage by countering the self-cast shadow that would otherwise occur if the colouring was uniform. A uniform colour would make the shape of the animal stand out, because the upper parts would reflect the sun more than the lower parts and, betray the shape of the body. A darker upper side counterbalances this self-shadowing effect of the sun by reducing the amount reflected by the upper side. This enhances background matching and hides the shape of the body better.

So, under the above definition of brown, any coat that has a clear reddish colour with black points is considered bay. On the other hand, any coat that has black countershading with black points is considered brown.

For our purposes we can stick to the general idea that a brown horse is one that is lighter than black, but darker than bay, and with black points. However, until a clearer genetic definition is confirmed and established, we will have to accept that this colour is open to interpretation.

How Rare?

So now that we have established the colours that Arabians can be, let us consider how common or rare each one is. The following is based on visual information from the larger herds of desert Arabians kept by some Bedouin, and from modern Arabian registries.

The most common colour for Arabians is bay, with approximately just over a third of Arabians being that colour. Grey, the next most common colour, accounts for just under a third. The remainder (approximately also a third) includes chestnuts, which constitute approximately 15% of all Arabians, and blacks and browns at around 20%.

There are very few rabicano (often called roan) Arabians, which makes this colour the rarest. Certainly rarer than black.

You will notice that the browns and blacks have been lumped together because, as mentioned above, it is often difficult to tell the difference between the two. As the approximate figures above are based on visual inspection, we have to allow for an element of individual opinion and judgement.

Different colours could be assigned to the same horse depending on the opinion of the individual conducting the inspection or, in some cases, if a DNA test is done.

Nevertheless, we can say that black Arabians are probably somewhere around 5%. So, while black is relatively uncommon, it is not so rare as to be too hard to find. That is good news for me!